Most of you must be surprised that I am speaking to you on this occasion. I myself was a bit surprised when Bonita asked me to do so – but only momentarily. Knowing Bonita, I realised that she was doing so in a quest for reconciliation and healing for our country – a goal she has pursued her entire life; often at tremendous sacrifice. I speak to you today, also in that spirit.

I want to state right up front that no one should have their life snuffed out in the brutal manner that has become the norm today in Guyana ; not Ronald Waddell nor anyone else. We must condemn in the strongest possible terms the recourse to violence to solve any dispute.

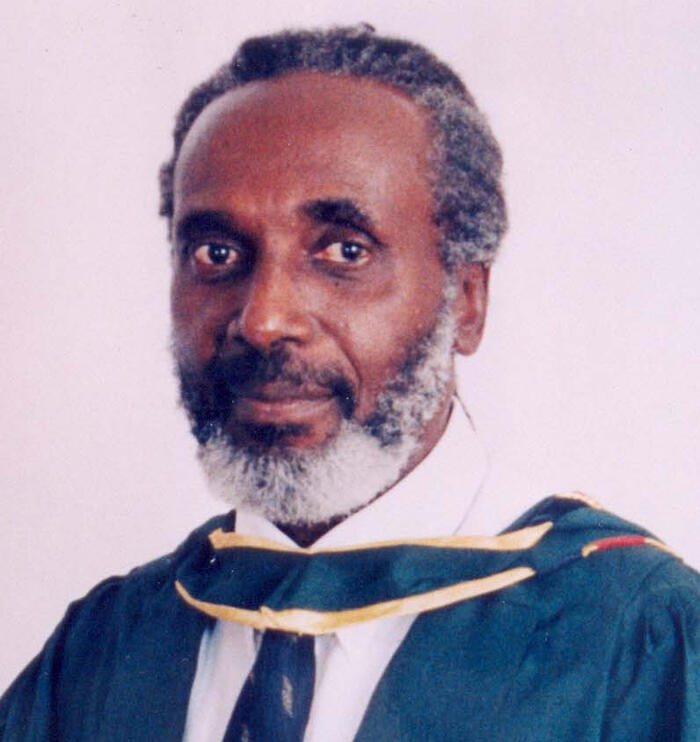

I first met Ronald Waddell in the mid-nineties when he was at the Stabroek News. A few years earlier, I had written a series of articles that Stabroek had published on the Gramscian concept of “hegemony” as a tool of oppression by the colonial masters and other ruling classes through conquest of the minds of the downtrodden. Ronald was taken by my observation that in the Caribbean, the Rastafarians, on their own, had identified the hegemony here as “ Babylon ” and had created what Gramsci called a “counter-hegemony” to deal with the debilitations of the colonial and post-colonial hegemony. Ronald Waddell, in his own life and praxis, sought to overcome that most insidious form of slavery by accepting the worldview of the Rastafari.

At the time I had been working with Hindu youths to deal with some of the effects of the hegemony on them and Ronald went with me to several discussions, encounters, and events amongst Indians. I remember his presence at a conference on “Suicide in the Indian Community” at the Cove and John Ashram in 1996 or so. I discovered that Ronald Waddell was a warm, caring and very intelligent individual deeply concerned about the problems of Guyana. His focus on the African community was simply a recognition that liberation, like charity, has to begin at home.

As a regular contributor to the letter pages of the newspapers then, I mentioned in one contribution the negative role played by the Mulatto/Coloured class in the imposition and maintenance of the hegemony among Africans in Guyana. Professor Clive Thomas and Andaie upbraided me in a published response for using a particular phrase; asserting that it had a “touch of odium” in regards to African Guyanese. Ronald Waddell took them to task not only to assert that they had misinterpreted me but for what he thought was their own intemperate use of language.

Ronald and I continued to have discussions on politics and society during the next few years, especially after the riots of January 12, 1998. I appeared on several of his programmes, “University on 9”. I witnessed his increasing despair at what he saw as the marginalisation of the African Guyanese from the levers of effective power in Guyana and more immediately, the widespread killing of young African males. His move from the WPA (position, since he was not a member) to the PNC as a candidate during the 2001 elections was in a sense an acceptance of realpolitik: he concluded that the PNC would obtain an overwhelming majority of the African vote and saw no benefit in fragmenting that vote. His vote could count, he hoped.

The result of the 2001 election was very traumatic for Ronald: he concluded that Indians would not switch their votes from the PPP even in the face of overwhelming evidence that the PPP was not even addressing their concerns, much less the concerns of Africans. In one of our conversations, I pointed out that in very similar circumstances (1992) Africans had acted in an identical fashion: it didn’t cut any ice with Ronald. We drifted apart from that stage and it was impossible for me to reconcile Ronald’s new politics with the person I knew.

I believe that Ronald’s drift from the politics of ballots to the politics of bullets represents a failure of our political system to deliver equality and justice to African Guyanese. From the beginning of my involvement with politics in Guyana, I had pointed out this failure but also that the system ultimately also failed Indians, Amerindians, and all other Guyanese. Ronald was not convinced about the dilemma of Indians– especially after 2001. He moved from blaming the system to blaming the people. The result, they say, is history.

I met Ronald for what was to be the last time when we bumped into each other at the “Groundings for Walter Rodney at Queens College” last year. I stated my vehement disagreement with the course he had chosen to rectify the wrongs he identified, some of which I accepted, caused by our political system. He said that he understood why I had to take the position about the pain of Indians but inquired as to who mourned the pain to Africans.

I believe that whatever our political convictions, whatever we may think about the politics of Ronald, we as Guyanese – regardless of which subset we choose to define ourselves – have to accept that we must revisit our political system to ensure that it delivers what John Rawls defines as the prime requisite for any social institution: JUSTICE. Or we can be assured of creating other Waddells – sensitive and caring men and women driven to nihilism in frustration at the manifest injustices around us.

In pursuit of that goal, however, let us heed the call of Bonita Harris, the widow of Ronald, for us to reject violence in all its manifestations, not only in politics but within all our relationships. It has been said that the old policy of “an eye for an eye” will leave us all blind in the end. Let us remember the Ronald of old and work towards addressing our disagreements and problems in a peaceful manner, so that no other Guyanese, or their families, will be left blind. As the hymn reminded us, all of us have been dragged to this Babylon, and we all have reason to weep as we remember our Zions. Let us reject violence as we strive to recreate a new Zion for all of us. My sincere condolences to Bonita and all the members of the family of Ronald Waddell. God Bless Guyana.